Fast, good, cheap: pick two

In this plague time, it might be an occasion to reflect on your beliefs and actions and make adjustments to the philosophies by which you live.

When it comes to food, re-evaluating your approach can be healthy at the same time it’s enlightening — especially in this era where we should be concerned about the people in the frontlines of service, whom we too often under-value.

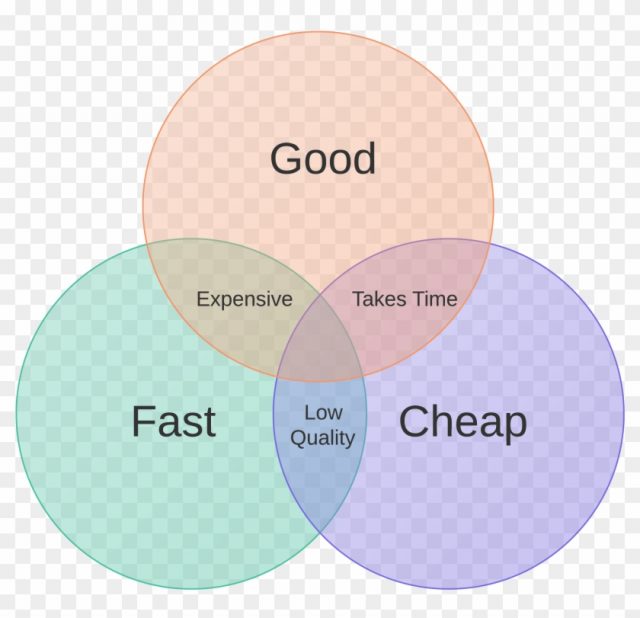

There’s a saying – “You can have it fast, you can have it good, you can have it cheap: pick two” – that is variously referred to as the “iron triangle” or the “triple constraint triangle.”

For everyone from project managers to industrial designers to software developers, the triangle, also taking the form of a nifty Venn diagram, as above, is a signifier of the struggle between those opposing forces of quality, speed and cost.

With respect to food, they would appear to align themselves.

But do they?

Let’s consider the ubiquitous “fast food.” You often hear someone ask, “Where can I get a cheap meal quickly?”

Cheap and fast food was available in the United States – pennies for a hamburger – as early as the 1920s, but its full-blown impact coincides with North American car culture. The post-World War II era’s booming U.S. economy saw automobiles, especially in the United States, became more affordable. Eventually, supper became a moveable feast as it shifted from the dining room table at home and onto the road.

As the network of roads and highways evolved and intensified, restaurants popped up at basket-weaves and highway interchanges. At those points near the highway on-ramp, you didn’t even have to get out of your car to have a meal: at a drive-in restaurant, a burger, fries and a shake appeared at your car window in minutes – thanks in part to car-maker Henry Ford and factory production-line food preparation, concepts of uniformity, centralized food management, pre-cooking and a mentality that faster was better.

Those same principles are at play, via economies of scale and rigid cost controls, in keeping fast food some of the cheapest possible. Issues around volume, standardization, inexpensive mass-produced (and lesser quality) ingredients, cheap fuel and transportation, outsourcing, and minimal labour costs are responsible.

Inexpensive food can be served quickly, but the question remains: is it good? While all three terms have a relative value – that is, you might find it inexpensive and delicious; someone else may not – the nature of its basic and minimal preparation, usually with little value added, can be an argument that it is not “good” on several levels which are not germane here.

Now, let’s assume that achieving “good” when it comes to food requires an investment of time, so the product – a freshly ground, hand-formed hamburger that, let’s say, blends beef and pork will necessarily have to be more expensive. The patty is not a uniform, frozen disk that was extruded and factory-made but is ground at the restaurant (or comes from a butcher), seasoned, formed and grilled by a cook.

The care and attention – not to mention the freshness, I can guarantee you – will result in a burger that the majority of diners will agree tastes better – and “good.” And that is not taking into consideration a bun that the restaurant makes (perhaps over the course of two days) and the condiments and sauces that another cook makes in-house as well.

This burger is not going to take much longer to prepare after you order it, though it could be considered “quick” compared to, say, cooking a more complex dish that has several components.

Because the burger has so many more points at which value has been added – and has better ingredients – it will cost more. Although the burger is relatively fast, it will cost more – and certainly more than a fast-food burger.

Many of us look for food that is good and affordable. But good food is not – nor should it be – necessarily “cheap.” Answering that previously posed question of where to get cheap food quickly requires thinking about how the three triangle elements work together and should prompt a thought or two in us about the values and “picks” that guide choice.

[Image: pikpng]