Two Calves Standing

A year or so ago, during winter, I visited a relatively new farm and addition to the food landscape that was started by former Waterloo Region-based restaurateur and culinary instructor Bryan Izzard.

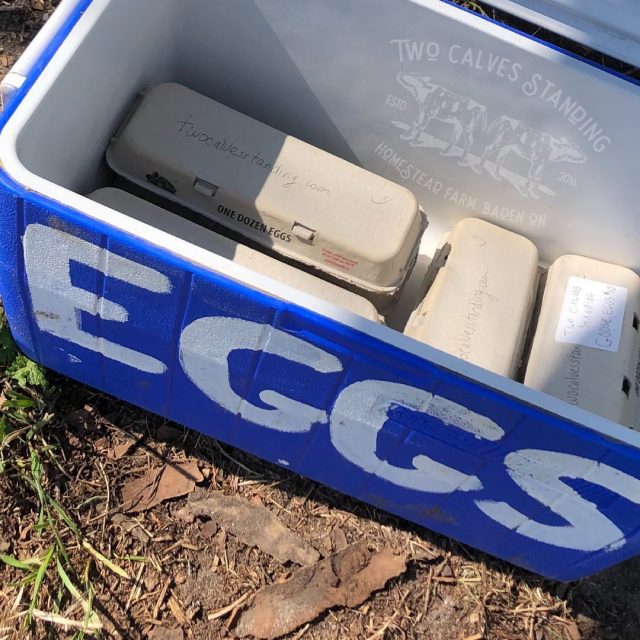

I recently re-visited the Baden farm, called Two Calves Standing, for a curbside pickup of some of the meat raised on the farm. And the weather was much warmer!

To give you an introduction to Izzard and Two Calves Standing, I’m posting a story originally published in the Waterloo Region Record.

*****

It’s mid-afternoon and 3-degrees C. on a grey, overcast Friday, but a stiff north wind blustering across open fields makes it feel like -9.

I’m shivering beneath a row of pines watching Bryan Izzard, medicine in hand, chase a Red Wattle in hopes of applying it. The agile critter has other ideas.

The pig is a member of a small porcine herd, or a drift, that Izzard oversees at his farm, Two Calves Standing, in Baden, Ontario, seven kilometers north of Highway 8.

Izzard, a long-time culinary figure in Waterloo Region, has only been farming since 2017. In that short time, he’s learned a lot about the travails of animal husbandry, the surprising wily nature of pigs – and himself.

“I’ve always believed it’s important to connect people with where their food comes from, so they appreciate the value of the process,” says Izzard. “I’ve also learned that farming on a small scale is tough financially. I’d like people to understand that too.”

The farm is 12 acres on which he produces naturally raised pork and beef. Though the farm is too small to serve many grass-fed cattle, he has 38 pigs, including 18 sows, along with goats and emus.

Izzard is in the middle of a steep learning curve but seems equal to the task. “I’ve been testing, and it seems that heritage pigs, Red Wattles, are the best fit. They’re my focus, and I can raise them naturally.”

For the kids’ culinary camps he runs in a few cities, Izzard buys ingredients from local farmers: Two Calves Standing is a sort of extension of that educational project. “The kids’ passion for creating cool food was a launching pad for sneaking lessons in about understanding where food really comes from.”

The culinary camps will be enriched with the on-farm cooking classes he hopes to offer in the future.

As for the farm’s name, it harkens to a particularly stressful moment when he was starting out and nursing a couple of sick calves: he entered the barn in the morning to see them standing and knew they had recovered. “I had been doubting myself, but I thought then that maybe I can do this.”

He has always respected that curve, however. His learning began when he had partnered with the farmer, a mentor, who worked the property before him, adding that he had a lot of work to do when he acquired the farm and started running things himself. That meant a lot of research and asking a lot of questions.

When you stand – perhaps especially in frigid, wintry conditions when the landscape is most desolate and bleak – and look at the horizon and see nothing but fields and farmland, you can understand Izzard’s concern with sustainability. “How do we protect our farmland and our planet for human use beyond the next several years,” he asks?

It’s an inherent systemic contradiction that should give us pause: in order for people to pay a premium for sustainable food raised like these animals – whose rich manure and rooting, let’s not forget, improves the soil for rotational crops – Izzard recognizes that the end product has to taste very, very good.

That’s where the Red Wattles enter the picture.

A breed designated by the North Carolina-based Livestock Conservancy as threatened, Red Wattles have distinctive folds of flesh waggling from each side of their neck. “They’re a very hardy breed and easy to raise, especially for year-round outdoor growing,” Izzard says.

Basically, a heritage breed pig must be a true genetic breed and when mated together reproduce the breed type. Izzard also has Ossabaw Island pigs, an ancient breed on the endangered list according to the Conservancy, an organization which works closely with Rare Breeds Canada.

Heritage pigs must also have access to open pasture and diets allowing them to exhibit natural omnivorous – and pig-like – behaviour; they must be free from routine prophylactic antibiotics as well as free from administered synthetic or natural growth promoters.

In each of the three or four breeds he raises, Izzard says there are different flavours. “The Red Wattle is almost a cross between beef and pork in taste, texture and marbling. They’re leaner too.”

He says they’re the best tasting pigs in North America. Ultimately, the flavour’s the thing and samples I ate were delicious. Yet farming is freighted with much more: sustainability, traceability and food security, how food choices impact health and community and the perspective a farm offers, especially for city folk – and new farmers.

Reflective, Izzard describes a sunset he observed from about the same frosty vantage point I had under the pines.

“I realized I was getting caught up in trying to get things done and forgot to appreciate the richness of this,” he says. “I watched that beautiful pink sunset for just five minutes and thought about how fortunate I am.”