A cheesy way to start your weekend

A nip or two of cheese and a crisp, cold glass of wine go well together despite wine connoisseurs who claim cheese is too salty to be paired with their favourite beverage.

Add a shaded deck cooled by a light summer breeze and conditions are perfect for this match made in heaven, I say.

In Ontario — and in fact here in Waterloo Region — we have superlative cheese-makers from Mountainoak and Gunn’s Hill to Ruth Klahsen at Monforte Dairy in Stratford, who has truly helped change the cheese conversation in Canada.

The thing about cheese is that it has a wonderfully long history — and it makes for complications.

Charles DeGaulle, President of France from 1959 to 1969, moaned about trying to rule a nation that produced hundreds of different cheeses, but choice is precisely one of the beauties of cheese. Both France and England produce over 500 kinds.

And some bizarre choices there are. In the Monty Python “Cheese Shop Sketch,” John Cleese (whose real name is John Cheese) effortlessly recites the names of 43 cheeses, including Venezuelan beaver cheese.

You could sniff out some Vieux Boulogne, a cow’s milk cheese aged nine weeks and washed in beer, which was once dubbed the “world’s smelliest cheese.”

Or how about a moose milk cheese from Sweden once produced thanks to three cows named Gullan, Haelga, and Juna? Made only between May and September, the cheese purportedly sells for $580 per pound (though it is anyone’s guess what kind of wine best goes with moose milk cheese). In England, a truffle-stuffed Brie once sold for $94 per kilogram.

Other rare alternatives are Ossau-Iraty, an unpasteurized ewe’s milk cheese made by Basques, or Bleu de Termignon in the French Alps which was once made from eight rare cows by a single woman nearly 100 years old.

Italy’s Basilican Podolico Caciocavallo also fetches extremely high prices because of the rare breed of podolico cows.

Yes, cheese history is as long as its flavours are varied. The first cheese production likely coincides with humankind’s domestication of animals around 10,000 BC. Archaeological evidence of cheese-making has been found in Egyptian tombs dating to 2,000 BC, while Homer’s “Odyssey” (eighth century BC) notes that the Cyclops tended sheep and made cheese. Cheddar has been made in Cheddar, England, since 1170.

Find a cheese that suits your taste

Conventionally, wines produced in the same location as the cheese are the best match, but don’t let hide-bound rules restrict your cheese enjoyment.

More tannic wines (“strong tea-like” dryness in the mouth) need the sharp bite of cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano, while strong, salty cheeses cry out for sweeter dessert wines.

Here are some classic combinations: French Munster meets beautifully an Alsatian Gewurztraminer, while Reblochon and a Chateauneauf-du-Pape are a lovely team. Creamy goat cheeses tantalize with sauvignon blanc, and Spanish Manchego goes perfectly with a Rioja or a glass of amontillado.

Roquefort or Stilton demand Sauternes or port, just as a chardonnay marries well with Brie and Camembert (but watch moldy rind which can ambush the wine). Sparkling wines can stand up to buttery triple-crème Saint Andre.

Loving your cheese

Young cheeses are less flavourful, and the best cheeses have natural rinds or are cloth-covered (not wax). Never freeze cheese: store it in the warmest part of your fridge (and never in plastic wrap) in waxed paper or parchment in a Tupperware container (there is a product called “cheese paper” you could try).

The harder the cheese, the longer it will remain fresh. Serve cheese at room temperature. Honestly, your cheese doesn’t really like to be taken in and out of the fridge very often.

A pox on Louis Pasteur

Turophiles (serious cheese lovers) maintain that the best cheeses are made from fresh raw milk—right from the sheep, cow, or goat and teeming with live organisms and flavour.

Louis Pasteur, the French chemist who posited the germ theory, experimented with the first pasteurization in 1862—in doing so, he ruined cheese forever. Yes, he was instrumental in killing bad bacteria, viruses, yeasts, and molds with a heating process that has saved millions of lives, but in pasteurizing raw milk (cooking it below the boiling point), a lot of the good bacteria—and flavour—are neutralized.

Raw, unpasteurized milk cannot be sold in some countries, but raw-milk cheese that has been aged for 60 days is available. The aging process reduces the potential harmful effects of the cheese. Soft, unripened cheeses must be made from pasteurized milk.

The appetizing way cheese is made

Cheese starts with the lacteal secretion of any mammal and is a process of controlled “rot.” Adding streptococci (the same family that causes strep throat) or lactobacilli bacteria to the milk converts sugars to lactic acid.

Introducing rennet (an enzyme from the animal’s stomach) then causes the solid curds to clump together and separate from the liquid whey (today, many cheeses are made with vegetable rennet). The bacteria starter keeps working and will be important to the cheese’s final flavour.

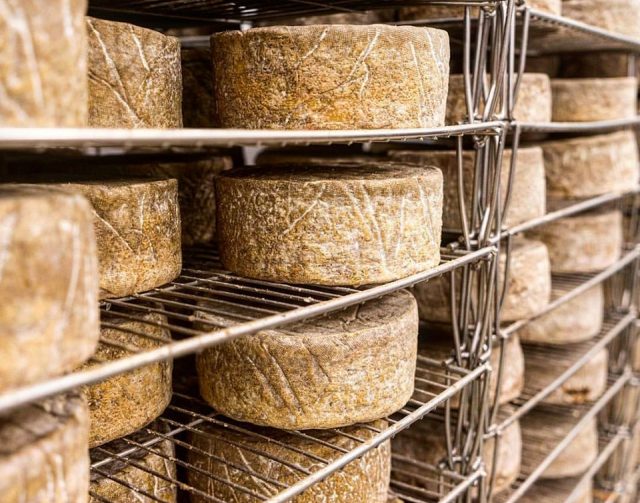

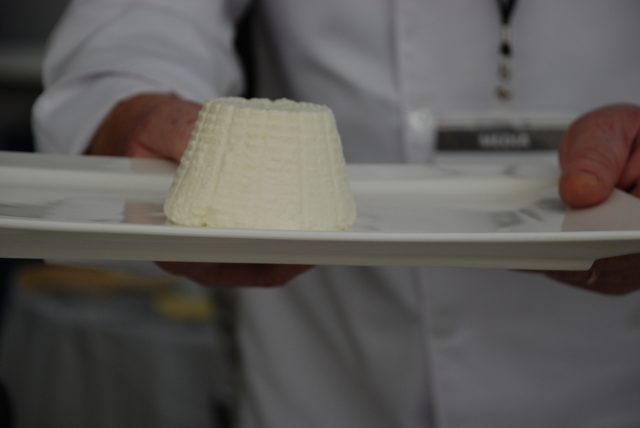

Next, reheating and agitating the curds causes them to combine. The cheese is then salted to slow the action of the starter and give the cheese a longer life (that is, salts slows the spoilage) before being pressed and shaped in molds. Some cheeses have been made into huge wheels—Queen Victoria was once given a 450 kilogram-wheel of Cheddar for a birthday gift.

Finally, the cheese is allowed to age or ripen (or continue to rot if you like) in storage rooms (originally caves in the ground) of varying humidity. French Comte cheese ages for as long as 36 months. As the cheese “breaks down,” it gains flavour. Naturally occurring bacteria, flatulent little devils that they are, will eat lactic acid which they pass as the carbon dioxide that forms the “holes” of the particular cheese.

Roquefort cheese features Penicillium roqueforti: spores from moldy bread are added to the curd. This famous cheese from southern France is “needled” with a metal skewer introducing oxygen as food for bacteria and causing blue veins.

Yet other cheeses are given a bath (lavee) in wine, beer, or brandy to help them age and often give them quite pungent aromas. Epoisses de Bourgogne, a bathed cow’s milk cheese, was one of Napoleon’s favourites. Cheeses like orange Cheddar are often coloured with annatto, the seed of the South American achiote shrub.

Starting off as chunky cheeses, Brie and Camembert rot from the outside in, rather than the other way round, thus forming a crust outside and turning the interior almost liquid. At the very heart of the best Brie, is a kernel of chalkiness the French call “l’ame:” the soul of the cheese.

Attaining “Master Cheesemonger” Status

If it is in your soul to become a “maitre-fromager,” you need to join the Guilde de Saint Uguzon, a French organization that is more than 800 years old.

[Image/Monforte Dairy Facebook]