Cartoon Robin Hood signed my recipe book

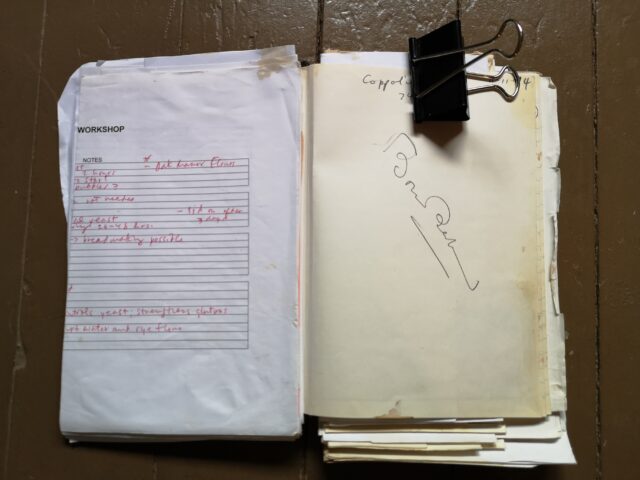

I have a very old, bulging-at-the-seams book of notes and recipes from the restaurant that, at once, makes me smile and gives me a little jab or twinge of melancholy.

It’s black with a faux leather design held together by a large Acco binder clip which keeps corralled (just barely) a jumbled stew of innumerable slips of paper, envelopes (some empty), notes, clipped recipes and a flotsam-and-jetsam of ideas and hoped-for inspiration.

It’s not a rectangular book any longer, its now-misshapen spine hacked and tattered and bowed – the edges and corners are softly rough: like smooth suppleness through years of clutching it. Now near talismanic, it somehow gives me great pleasure to hold it and flip through its worn and slightly oily pages. Hell, it gives me pleasure just to look at its battered boards.

Inside the true business part of the notebook are a few diagrams of plate design – amateurish, for sure – and the basic recipes that I was responsible for: bread, pizza dough, Caesar dressing, cheesecake, tiramisu, chili oil, a delicious lemon tart which demanded intense focus to get just right in terms of the creaminess of the filling and the crispiness of the pâte sablée, which, I was told, was a rather forgiving short-crust pastry dough.

The pages are dog-earred and slaughtered with spills of oil and sauces and yellowed and discoloured from even the short time I spent in the hurly-burly of prep time as I was learning how to do things on the line and in prep. There are lists of dozens of menu items and ingredients in the back pages – what I saw as an overwhelming regimen of duties and responsibilities, coded with “(D)” or “(EOD)” or “(W)” or “(TW)” for daily, end-of-day, weekly or twice-weekly.

I don’t recall if the annotations were my hastily added hieroglyphs or Entremet’s suggestions, but, like hieroglyphics, a foreign language, I can’t be entirely sure of how to interpret them looking back today: they represent a sort of code and jargon short form of my past quite some time ago. They stir a question: what if I had stuck with it and pursued this idea I had had, this experiment I had undertaken, of making cooking a career?

There’s no answer.

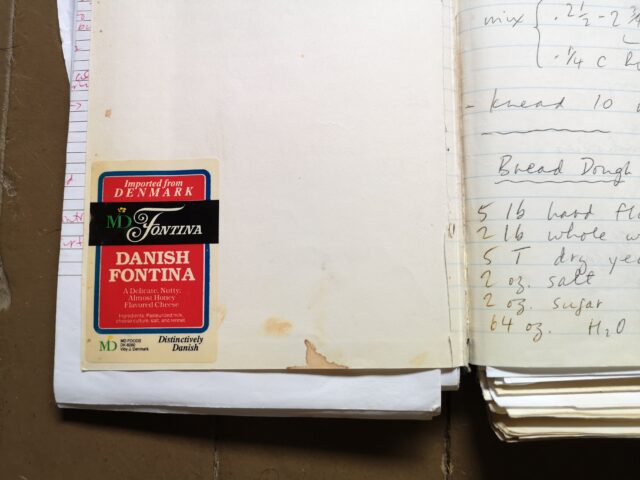

On the flyleaf of the notebook – if notebooks have a flyleaf – there is a colourful rectangular sticker, eight centimetres by five centimetres, from a wheel of cheese, nicely appended to the very bottom corner of the page: that, I am sure, was put there by wise-acre Entremet. It says, “Imported from Denmark. DANISH FONTINA” and is described as “A Delicate, Nutty Almost Honey Flavoured Cheese,” the upper-case letters reminiscent of a mid-18th century epistolary novel. It’s what I imagine Henry Fielding would write if he was in food marketing.

The cheese was used on one of our pizzas; it would make sense that that would have been the four-cheese variety we had on the menu at the time. But, that bit of a prank is just over the page from another addition to the notebook that has much greater and warm significance: whenever I unclip ACCO to rifle through the mess of papers looking for a recipe or an idea, the two not always linked, I flip to those opening pages and look at a signature that’s scrawled there – that of the late Stratford actor, the talented Brian Bedford.

That he signed my sloppy stained notebook is not what you might think it is. Cooks (but not me) are often asked, “What famous people have you cooked for?” I don’t recall many, actually. Periodically, celebrities and personalities of all magnitude would find themselves in Kitchener for one reason or another and the restaurant’s central location in the city and near cultural points of interest and its political hub meant they would drop in to eat at a decent venue like ours that could provide some privacy and anonymity. And it was just a very good place to eat.

That was not the case for Bedford, however. He and his partner, Tim McDonald, would travel from the lovely town of Stratford, about 30 minutes away, including during the winter when the Shakespeare Festival was in its sleepy off-season and therefore many of the town’s food outlets were dormant. The restaurant owner had previously cooked in Stratford and so I’m sure that there was a familiar relationship between them. There was that idea of the restorative nature of a restaurant – the relationship between host and patrons – I have previously mentioned elsewhere. I certainly don’t recall what Brian and Tim ate on those occasions, but I did prepare soups and salads that I knew were going to their table. Perhaps the odd dessert.

So, one snowy winter evening as they left by the restaurant’s back entrance, just outside of which the dishwasher was cursing as he chopped firewood for the pizza oven, which meant walking right in front of the pass of the open kitchen and the cooks. I grabbed my notebook without really thinking much about how I was going to blurt out, “Mr. Bedford! Could you sign my book?” I don’t think I even said “please.” I’m sure he was surprised, and perhaps a bit alarmed, by the sudden request, but he was gracious and, smiling from behind a large, fluffy scarf twirled dashingly around his neck and shoulders, he took off his gloves, accepted the pen I was offering and signed “Brian Bedford.”

I knew that the British-born Bedford, who died in 2016, was something of a giant of the stage. He was in acting school with Alan Bates, Albert Finney and Peter O’Toole. Good Lord. The man was a Shakespearean master who played opposite Gielgud in The Tempest, was Richard III, was a stellar Malvolio in Twelfth Night and who also had roles in Moliere’s Tartuffe and Wilde’s wonderful The Importance of Being Earnest. I may be wrong, but I think he had either the role of Vladimir or Estragon in one of my favourite plays ever, Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

And now, here he was standing in front of me, having just eaten some food that I had prepared for him, a Tony-award winner and an actor who had gained more of those Tony nominations than just about anyone. I guess I was a bit star-struck. However, as terrific and accomplished as his stage-craft might have been, it was for another performance entirely that I had acted so spontaneously and frivolously — and that was on behalf of my seven-year-old daughter.

You see, Brian Bedford was the voice of “Robin Hood” in the 1973 animated adventure and musical comedy, a film produced by Walt Disney Productions.

I wanted his signature for her because she loves the film to this day.

“Oo-De-Lally, Oo-De-Lally

Golly, what a day.”